Emma Darwin

Emma Darwin | |

|---|---|

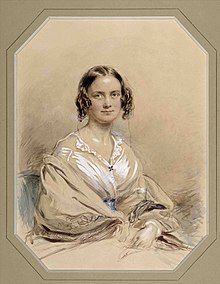

Darwin in 1840 | |

| Born | Emma Wedgwood 2 May 1808 Maer, Staffordshire, England |

| Died | 2 October 1896 (aged 88) |

| Resting place | St Mary's Church, Downe |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 10, including William, Annie, Henrietta, George, Francis, Leonard and Horace |

| Parent(s) | Josiah Wedgwood II Elizabeth (Bessie) Allen |

Emma Darwin (née Wedgwood; 2 May 1808 – 2 October 1896) was an English woman who was the wife and first cousin of Charles Darwin. They were married on 29 January 1839 and were the parents of ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.

Early life

[edit]Emma Wedgwood was born at the family estate of Maer Hall in Maer, Staffordshire, the youngest of seven[1] children of Josiah Wedgwood II and his wife Elizabeth "Bessie" (née Allen). Her grandfather Josiah Wedgwood had made his fortune in pottery, and like many others who were not part of the aristocracy, they were nonconformist, belonging to the Unitarian church. Charles Darwin was her first cousin; their shared grandparents were Josiah and Sarah Wedgwood, and as the Wedgwood and Darwin families were closely allied, they had been acquainted since childhood.[2]

She was close to her sister Fanny, the two being known by the family as the "Doveleys", and was charming and messy, accounting for her nickname, "Little Miss Slip-Slop".[2]: 9 She helped her older sister Elizabeth with the Sunday school which was held in Maer Hall laundry, writing simple moral tales to aid instruction and giving 60 village children their only formal training in reading, writing and religion.[2]: 17

The Wedgwoods visited Paris for six months in 1818. Though Emma was only 10 at the time, the strangeness and interest of arriving in France remained in her memory.[3]

In January 1822 the 13-year-old Emma and her sister Fanny were taken by their mother for a year at Mrs Mayer's school at Greville House, on Paddington Green, London, at what was then the semi-rural village of Paddington. Emma was by then "one of the show performers on the piano", to the extent that on one occasion she was invited along to play for George IV's Mrs Fitzherbert. After this time, Emma was taught by her elder sisters as well as tutors in some subjects.[4] For the rest of her life Emma continued to be a fine pianist, with a tendency to speed up slow movements. She had piano lessons from Moscheles, and allegedly "two or three" from Chopin.[5]

In 1825 Josiah took his daughters on a grand tour of Europe, via Paris to near Geneva to visit their Aunt Jessie (Madame de Sismondi, née Allen, wife of the historian Jean Charles Leonard de Sismondi) and then on. In the following year the Sismondis visited Maer, then took Emma and her sister Fanny back to near Geneva to stay with them for eight months.[6] When her father went to collect them he was accompanied by their cousin, Caroline Darwin, and also took Charles Darwin, Caroline's brother, as far as Paris, where they all met up again before returning home in July 1827. She was keen on outdoor sports and loved archery.[2]: 21

At Maer on 31 August 1831 she was with her family when they helped Charles Darwin to overturn his father's objections to letting Charles go on an extended voyage on the Beagle. During the voyage Charles' sisters kept him informed of news including the death of Emma's sister Fanny at the age of 26, political developments and family gossip.[2]

Emma herself had turned down several offers of marriage, and after her mother suffered a seizure and became bedridden Emma and her older sister Elizabeth spent a lot of time nursing their mother, though with the help of many servants. Emma and Elizabeth took turns spending time away from their mother, and Emma spent several months each year away from home, staying with friends or family.[2]: 57–58

Marriage

[edit]

Emma Wedgwood accepted Charles' marriage proposal on 11 November 1838 at the age of 30, and they were married on 29 January 1839 at St. Peter's Anglican Church in Maer. Their cousin, the Reverend John Allen Wedgwood, officiated the marriage.[7]

After a brief period of residence in London, they moved permanently to Down House, located in the rural village of Down, around 16 miles (26 km) from St Paul's Cathedral and about two hours by coach and train to London Bridge. The village was later renamed Downe.[8]

Charles and Emma raised their 10 children in a distinctly non-authoritarian manner, and several of them later achieved considerable success in their chosen careers: George, Francis and Horace became Fellows of the Royal Society.[9]

Emma Darwin is especially remembered for her patience and fortitude in dealing with her husband's long-term illness. She also nursed her children through frequent illnesses, and endured the deaths of three of them: Anne, Mary, and Charles Waring. By the mid-1850s she was known throughout the parish for helping in the way a parson's wife might be expected to, giving out bread tokens to the hungry and "small pensions for the old, dainties for the ailing, and medical comforts and simple medicine" based on Dr. Robert Darwin's old prescription book.[citation needed]

In a letter dated 5 July 1844, Charles Darwin entrusted to Emma the responsibility of publishing his work, in the case of his sudden death.[10] Charles lived and published On the Origin of Species in 1859.

Emma often played the piano for Charles, and in Charles' 1871 The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin spent several pages on the evolution of musical ability by means of sexual selection.[citation needed]

Religious views

[edit]Emma's religious beliefs were founded on Unitarianism, which emphasises inner feeling over the authority of religious texts or doctrine. Her views were not simple and unwavering, and were the result of intensive study and questioning.[11] Darwin was open about his scepticism before they became engaged, and she discussed with him the tension between her fears that differences of belief would separate them, and her desire to be close and openly share ideas. Following their marriage, they shared discussions about Christianity for several years. She valued his openness, and his genuine uncertainty regarding the existence and nature of God, which gradually developed into agnosticism. This may have been a bond between them, without necessarily resolving the tensions between their views.[11]

By early 1837 Charles Darwin was already speculating on transmutation of species. Having decided to marry, he visited Emma on 29 July 1838 and told her of his ideas on transmutation. On 11 November 1838, he returned and proposed to Emma. Again he discussed his ideas, and about ten days later she wrote to him:

"When I am with you I think all melancholy thoughts keep out of my head but since you are gone some sad ones have forced themselves in, of fear that our opinions on the most important subject should differ widely. My reason tells me that honest & conscientious doubts cannot be a sin, but I feel it would be a painful void between us. I thank you from my heart for your openness with me & I should dread the feeling that you were concealing your opinions from the fear of giving me pain. It is perhaps foolish of me to say this much but my own dear Charley we now do belong to each other & I cannot help being open with you. Will you do me a favour? yes I am sure you will, it is to read our Saviour's farewell discourse to his disciples which begins at the end of the 13th Chap of John. It is so full of love to them & devotion & every beautiful feeling. It is the part of the New Testament I love best. This is a whim of mine it would give me great pleasure, though I can hardly tell why I don't wish you to give me your opinion about it."[12]

Darwin had already wondered about the materialism implied by his ideas.[13] The letter shows Emma's tension between her fears that differences of belief would separate them, and her desire to be close and openly share ideas. Emma cherished a belief in the afterlife, and was concerned that they should "belong to each other" for eternity.[11] The passage in the Gospel of John referred to in Emma's letter says "Love one another" (13:34), then describes Jesus saying "I am the way, the truth and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me" (14:6). Desmond and Moore note that the section continues: "Whoever does not abide in me is thrown away like a branch and withers; such branches are gathered, thrown into the fire and burned" (15:6).[14] As disbelief later gradually crept over Darwin, he could "hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine."[15]

Following their marriage in January 1839, they shared discussions about Christianity for many years. They socialised with the Unitarian clergymen James Martineau and John James Tayler, and read their works as well as those of other Unitarian and liberal Anglican authors such as Francis William Newman whose Phases of faith described a spiritual journey from Calvinism to theism, all part of widespread and heated debate on the authority of Anglicanism. In Downe Emma attended the Anglican village church, but as a Unitarian had the family turn round in silence when the Trinitarian Nicene Creed was recited.[11]

Soon after their marriage, Emma wrote to Charles "while you are acting conscientiously & sincerely wishing, & trying to learn the truth, you cannot be wrong",[16] and although concerned at the threat to faith of the "habit in scientific pursuits of believing nothing till it is proved", her hope that he did not "consider his opinion as formed" proved correct. Methodical conscientious doubt as a state of inquiry rather than disbelief made him open to nature and revelation, and they remained open with each other.[11][16]

Later life and the Darwin grounds

[edit]

Shortly before she turned 74, her husband Charles died at 73 on 19 April 1882. Subsequently, Emma spent the summers in Down House. She bought a large house called The Grove on Huntingdon Road in Cambridge, and lived there during the winters. Emma Darwin died in 1896. Her son Francis had a house, which he named Wychfield, built in the grounds of The Grove. He lived there during most winters, spending summers in Gloucestershire. Emma's son Horace also had a house built in the grounds, and named it The Orchard.[17][18]

The Grove is now the central building of Fitzwilliam College,[19] and provides common room facilities for graduates, Fellows and senior members.[20] In January 2009, Cambridge City Council gave the College planning permission to demolish its gatehouse, Grove Lodge, which now forms part of Murray Edwards College. After local residents and academics expressed concern and there was a campaign against the demolition, the college council decided to reconsider possible alternative uses;[21] their decision at the end of September 2009 was to keep and refurbish Grove Lodge.[22][23] Architects, consultants and builders were appointed for conversion work,[24] which when completed in September 2011 provided five new studies for Fellows.[25]

Children

[edit]- William Erasmus Darwin (1839–1914)

- Anne Elizabeth Darwin (1841–1851)

- Mary Eleanor Darwin (1842)

- Henrietta Emma "Etty" Darwin (1843–1927)

- George Howard Darwin (1845–1912)

- Elizabeth Darwin (1847–1926)

- Francis Darwin (1848–1925)

- Leonard Darwin (1850–1943)

- Horace Darwin (1851–1928)

- Charles Waring Darwin (1856–1858)

The Darwins (after Charles' death in 1882, Emma and Francis) also brought up Francis' son Bernard Darwin (1876-1961) after the death of Bernard's mother a few days after he was born.

Cultural references

[edit]In 2001 a biography of Emma was published written by Edna Healey, though it has been criticised for attempting to give credit to Emma for her husband's ideas, whereas other historians agree she had little, if any, scientific input.[citation needed]

In 2008 Mrs Charles Darwin's Recipe Book was published, with profits going to the Darwin Correspondence Project at Cambridge University.[26]

The 2009 film Creation focuses in part on the relationship between Charles and Emma. Emma was played by Jennifer Connelly.[citation needed]

A boarding house at Shrewsbury School is named in her honour.[27]

Darwins buried at Downe

[edit]Eight members of the Darwin family are buried at St Mary's Church, Downe. Darwins buried at Downe include: Bernard Darwin and his wife Elinor Monsell, who taught her husband's cousin Gwen (Darwin) Raverat, engraver and author of Period Piece; Charles Waring Darwin; Elizabeth Darwin, "Aunt Bessy"; Emma Darwin, Charles Darwin's wife; Erasmus Alvey Darwin; Mary Eleanor Darwin; Henrietta Etty Darwin, later Litchfield, "Aunt Etty". Emma Darwin's sister Elizabeth Wedgwood and Aunt Sarah Wedgwood are also buried together at St Mary's.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Social history of the piano

- Emma Darwin (novelist)

- List of coupled cousins

- Darwin–Wedgwood family

- Emma Darwin: A Century of Family Letters

Notes

[edit]- ^ Desmond & Moore 1991, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d e f Loy, James D., Loy, Kent M. (2010). Emma Darwin: A Victorian Life. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813037912.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Litchfield 1904, p. 145.

- ^ Litchfield 1904, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Litchfield 1904, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Litchfield 1904, pp. 216–219, 242–245.

- ^ Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 269, 279.

- ^ "Letter 637 — Darwin, C. R. to Darwin, E. C., (24 July 1842)". Darwin Correspondence Project. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012.

- ^ "List of Fellows of the Royal Society / 1660 - 2006 / A-J" (PDF). Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "letter from Charles Darwin to Emma Darwin, 5th July 1844". Darwin Correspondence Project.

- ^ a b c d e "Darwin Correspondence Project - Belief: historical essay". Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 441 — Wedgwood, Emma (Darwin, Emma) to Darwin, C. R., (21–22 Nov 1838)". Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- ^ Darwin 1838, p. 166

- ^ Desmond & Moore 1991, pp. 269–271

- ^ Darwin 1958, p. 87.

- ^ a b "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 471 — Darwin, Emma to Darwin, C. R., (c. Feb 1839)". Archived from the original on 23 April 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ^ Freeman 1984, pp. 55–57

- ^ Freeman 2007, p. 293

- ^ "Architecture". Fitzwilliam College - University of Cambridge. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Common Rooms". Fitzwilliam College - University of Cambridge. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Latest news from Cambridge & Cambridgeshire. Cambridge sports, Cambridge jobs & Cambridge business - Darwin site may be used as art gallery". Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ^ http://www.savegrovelodge.co.uk/?p=88[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Castle Liberal Democrats, Cambridge | CAMPAIGNERS CELEBRATE VICTORY AS DARWIN LODGE SAVED". Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ "Architecture, Design and Historic Buildings Advice: Murray Edwards College, Cambridge: Grove Lodge". Paul Vonberg Architects. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 30 June 2012" (PDF). Murray Edwards College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Swaine, Joe. "Revealed: the recipes that fuelled Charles Darwin" The Telegraph 21 December 2008.

- ^ Shrewsbury School. "Our Houses".

References

[edit]- Browne, E. Janet (1995), Charles Darwin: vol. 1 Voyaging, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 1-84413-314-1

- Browne, E. Janet (2002), Charles Darwin: vol. 2 The Power of Place, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 0-7126-6837-3

- Darwin, Charles (1837–1838), Notebook B: [Transmutation of species], Darwin Online, CUL-DAR121, retrieved 20 December 2008

- Darwin, Charles (1838), Notebook C: [Transmutation of species], Darwin Online

- Darwin, Charles (1887), Darwin, Francis (ed.), The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter, London: John Murray, retrieved 4 November 2008

- Darwin, Charles (1958), Barlow, Nora (ed.), The Autobiography of Charles Darwin 1809–1882. With the original omissions restored. Edited and with appendix and notes by his granddaughter Nora Barlow, London: Collins, retrieved 4 November 2008

- Desmond, Adrian; Moore, James (1991), Darwin, London: Michael Joseph, Penguin Group, ISBN 0-7181-3430-3

- Freeman, R. B. (1984), . Darwin Pedigrees, London: printed for the author, retrieved 15 September 2009

- Freeman, R. B. (2007), Charles Darwin: A companion (2d online ed.), The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online, retrieved 18 June 2008

- Litchfield, Henrietta Emma (1904), Emma Darwin, wife of Charles Darwin. A century of family letters, London: John Murray, retrieved 18 February 2013

Further reading

[edit]- Healey, E. Wives of fame : Mary Livingstone, Jenny Marx, Emma Darwin London : Sidgwick & Jackson, 1986. 210 pp. (see also Emma Darwin, above.)

- Healey, Edna. Emma Darwin: The inspirational wife of a genius London: Headline, 2001. 372 pp. ISBN 0 7472 6248 9

External links

[edit]- Emma Darwin at Find a Grave

- Emma Darwin's diaries 1824-1896

- UKRC GetSET Women blog "featuring" Emma Darwin